As new technologies that advance society are developed and GDP steadily increases, material possessions grow proportionally in parallel. Progress leads to improved healthcare, more accessible education, and greater economic opportunities, but also elevated expectations for what is enough. The computer was once so expensive (and large) that only the government and rich universities could afford them. Now everyone has one in their pocket. Today we buy five times as much clothing as we did in 1980. This article titled “20 modern luxuries you never knew you needed (until now)” includes items like a “chic, compact towel warmer” and "app-controlled smart mug that can keep your lattes perfectly piping hot for up to 1.5 hours”. These are not actual luxuries like a Ferrari or Audemars Piguet timepiece, but rather reasonably-priced unnecessary BS consumer goods that make the upper-middle class feel like they’re upper class.

There are two separate issues here. We keep moving the goalposts for what we think we need to live a good life, especially when it comes to physical goods. This is why we tell ourselves we need to cop the latest sneaker drop, have a different swim suit for each day of our sun-kissed beach vacation, and wait in line on the first day possible to upgrade our fully-functioning iPhone 13 Pro Max to iPhone 14 Pro Max.

It wasn’t always this way. Previous generations viewed non-functioning equipment as a temporary setback to be solved rather than a two-part sequence of chucking it into the trash and then immediately ordering a new replacement on Amazon:

It was the repair-it generation (up until 1980’s or thereabouts)… More than proud, it reminded me of the generations I grew-up through, the generations of my grandparents and parents for whom nothing was irreparable, everything was repaired, refurbished, reused, recycled, repurposed… A couple of years ago my young (30-something) neighbour called around because their washing machine had broken. It was “really old though, and they didn’t think it worth repairing”—it was less than 3 years old and still in extended warranty. They called on me because I fix stuff, I cut my own hedges, cook my own food, rod my drains, that sort of thing, you know? Do stuff for myself and other people, not just buy stuff from other people because the battery doesn’t take a full charge in 30 minutes. I repaired the machine—it had a hairpin or three stuck in the pump. They bought a new machine anyway, the trauma of potentially being without for a few days and not knowing how to do a service wash at a launderette was too much. - Dr. John L Collins

Where do we go from here?

Being aware that we, as a collective society, buy too much stuff is only the first step. But how do we actually solve the problem? I idealize an environmentally-conscious consumer base that decides to drastically alter their shopping behaviors, but perhaps that’s exactly what it is - an ideal fantasy, rather than pragmatic reality. Do we just tell people to be happy with less?

Climate as a theme cuts across all industries and serves as the through line as we transition to a decarbonized, new economy. To understand how shopping shifts trends towards sustainability and what the circular economy even entails, I leaned on a wide range of perspectives: fashion designer, textiles business owner, excess inventory marketplace founder, and circular economy software founder. My goal was to find answers for the questions that continue to stump me:

What does the word “sustainable” even mean in the context of fashion and consumer goods?

What is the circular economy and how impactful can it be in the context of global warming?

Is the encouragement of secondhand shopping just a painkiller for the root problem of consumerism? Should we instead tackle the problem head-on by figuring out how to shift culture and what society values towards fewer possessions?

Framing the problem

The fashion industry contributes 10% of overall carbon emissions which includes associated industrial processes, logistics, and disposal. Over 70% of the overall GHG emissions from the fashion industry come from “energy-intensive raw material production, preparation, and processing”. A further 18% of potential abatement is comprised by the brand’s operations including the logistics of moving parts from their respective origins to the final destination of your home. An individual luxury handbag could source leather from the US, brass hardware from Germany, and get assembled in Florence, material evidence of how globalized and interconnected we are.

Critics of the fashion industry point to other types of harm beyond greenhouse gas emissions. To produce the 80 billion apparel items purchased every year, 79 trillion liters of water are consumed. Additionally, in a frenzy to maximize profit margin, brands, retailers, and manufacturers have perpetuated low wages, dangerous working conditions, and inadequate benefits.

It’d be disingenuous to isolate the fashion industry as the sole culprit fueling consumerism. Today, all mass-produced physical goods are manufactured via carbon-emitting processes to some extent. But the fashion industry frequently gets painted as the chief culprit in the climate crisis because of its obvious visibility in society and culture, but also head-turning stats like the average garment is worn only 7 times. How did we get to today where the average American owns 103 garments?

The answer is quite complex in this multivariable, highly connected system, but let’s take a closer look at one of the chief culprits: fast fashion. The growing category utilizes low prices and trend-seeking products along with promo-induced impulse buying to drive subsequent purchases. Within the category, there is no better company to case study than Shein, the $15B trend-pumping juggernaut based out of China.

The double-edged sword of “Innovation”

In Shein: The TikTok of Ecommerce, Packy McCormick inspects what’s under the hood of the growth engine that’s powering $100B in sales and literally thousands of new SKUs per day.

By leveraging big data, machine learning, and a vertically-integrated supply chain, Shein has been able to spot and then accelerate trends right as they’re emerging. By cutting out the middlemen in their customer-to-manufacturer business model (like Pinduoduo) and forcing every manufacturing partner to use their in-house supply chain management software, they’ve been able to truncate the time from design to production from three weeks to just three days. By algorithmically monitoring consumer behavior across search engines and social media and having full transparency into the manufacturer’s activity at any single moment, Shein has been able to achieve the closest thing to real-time retail.

The ability to not only track, but also control what’s going on with both consumers and manufacturers enables a powerful flywheel that results in a self-fulfilling prophecy of further consumption via impulse buying.

Imagine that a new item, designed based on Shein’s own and 3rd party data, goes live on the website, and immediately starts getting user behaviors correlated to sales (i.e. X number browsing product details, X number added to shopping cart). Based on taps, clicks, and sales, an algorithm doubles the production quota, which is immediately updated on the factory floor with extra materials automatically ordered. A second algorithm updates the weightings and recommends the item to more users with similar profiles. That’s impossibly fast to compete with. - Shein: The TikTok of Ecommerce

Although Packy does eventually get to the environmental impact of Shein towards the end, out of the entire 9,000 words in the piece, just 84 words (0.9% if you’re doing the math) are used to discuss how harmful fast fashion can be. We don’t need to have full transparency to Shein’s Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions or any equivalent to intuit its high-level impact on the environment. If a company can produce 18,349 new SKUs per day at a global scale then that implies two things: 1) they’re going to try and sell as much of it as possible and 2) not all of it is going to be sold. Overproduction and overconsumption are the hidden costs of Shein’s and the overall fast fashion industry’s success. In the conclusion, Packy says “Just like TikTok, Shein’s achievements in America are based upon serving the needs of young Americans better than American companies.” This is true if we’re “serving the needs” and measuring success in units of new users, average order value, and retention rate. But at what cost?

To many, Shein is a case study of impeccable innovation across software, supply chain, and marketing, but that is because the current economy doesn’t effectively value environmental impact into a business’ performance, just like how we measure the greatness of a country by GDP rather than well-being of its citizens.

Breaking down the circular economy

Now that we’ve examined the problem, it’s worth exploring some potential solutions. After all, this is a climate newsletter about spotlighting solutions rather than sitting on our asses and being doomers. In the next section, I’ll cover the composition of the circular economy and some exciting early indicators of a shift from the shopping equivalent of late-night munchies to conscious consumption. There are actually more parts of the circular economy movement than I thought and we’ll cover them all:

Secondhand / Resale

Trade-in

Repair

Off-price

Take-back / Recycling

To start, take a look at the left side of this diagram from thredUP’s 2022 Resale Report. There are quite a few different categories under the fashion umbrella:

Resale and Trade-In

One way of extending the lifetime of a clothing garment is to increase the number of uses by giving it a new owner. Instead of buying a new dress from an eCommerce brand or department store, purchasing secondhand effectively dampens demand for the manufacturing (and associated GHG emissions) of new clothing. There seems to be two models for resale today, peer-to-peer marketplace and brand-powered storefront. Like an online garage sale or consignment store, marketplaces like thredUP, Poshmark, and The RealReal allow individuals to easily upload items that they want to sell and then use search, categories, and recommendations to match products with a prospective buyer. Another model is to house a variety of alternative shopping modalities (P2P resale, trade-in, repair, take-back, recycling) behind the face of the brand. I find this approach compelling because offering alternative methods for buying and replacements for disposing under the centralized brand fits the mental model of the consumer who starts with the intent to buy or sell from a specific brand and only after figuring out how to actually do it.

To understand what’s really going on in the fashion resale world, I interviewed Sonia Yang, co-founder of Treet, a platform for brands to enable secondhand shopping.

1) What’s the single best or combination of solutions for both profitability and sustainability?

The most profitable and sustainable solution is the one that captures more secondhand buyers and sellers, which is an all-in-one P2P + Trade-In experience. This way, all customers can engage in a circular solution that best suits them, whether it's getting the best value for their item, or giving their item a second home as quickly as possible.

While P2P is the best method for individual sellers and has the lightest footprint with just the single leg journey, it lacks the instant redemption that Trade-In offers. Brands offering Trade-In take on the risk of inventory in exchange for store credit (at a lower price than P2P). For example, Patagonia’s Worn Wear program accepts used items, repairs them, and then sells them at a discounted price. Customers receive 50% of the resale value in store credit if it’s repairable. Otherwise it’s recycled to avoid ending up in a landfill.

2) Isn't there a conflict of interest by encouraging more spending and more purchasing via store credit with reducing carbon emissions? How do you reconcile this?

Ultimately, people will be spending their money somewhere. Our platform incentivizes customers to shop with our partner brands, most of which have strong sustainability initiatives, instead of other brands that may not.

Even with the purchase of a new item after the transaction, the transaction itself helped extend the life of an item and create a resale purchase instead of a new one.

By offering credit, we help extend the customer LTV with our brands and keep them returning to the brand. We see this cycle as a way to encourage brands to create higher-quality, more durable items, knowing that resale will be an essential part of their customer journey.

The positive feedback loop of higher-quality garments as a result of increased customer loyalty is super compelling. We’re in the early inning of brands using sustainable shopping methods as a competitive advantage.

3) What’s the most challenging part of the circular economy? Is it just one massive logistics problem of ensuring the goods are high-quality and then figuring out how to get it physically from point A to B?

The most challenging part of the circular economy is the learning curve that comes with it. It can take time to understand the culture of resale apps like Poshmark, and to know how to make offers, get the best deals, and ensure that sellers are trustworthy. At Treet, we try to make the shopping experience feel like customers are shopping from the brand directly, and we make selling so straightforward that even first-time sellers are surprised at how easy it is.

Off-price

Next I spoke to my friend Akash Raju, co-founder of Glimpse, a B2B marketplace for excess inventory. By efficiently distributing unsold goods to off-price sellers, they’re able to reduce the landfill waste by helping that inventory land in lower-priced retail storefronts.

1) How big is the off-price market?

The off-price market is a ~$200B market. This market is massive and in a way proportional to the size of the commerce market as a whole because as retail continues to grow, so will the amount of excess inventory.

2) What happens today with unsold goods at normal prices? What're the possible outcomes in terms of that item?

Right now, excess inventory is basically a brand's inventory that doesn't sell and can also encompass things such as returns and "seconds". For unsold inventory, it just sits in a warehouse, costing the brand warehouse fees. Brands try to offer discounts on their sites (e.g. flash sales) and other DTC mechanisms, but after this, they look to liquidate or sell to off-price, donate inventory, recycle raw materials. The worst case scenario is that the inventory is burned or sent to landfills.

3) Off-price allows unsold goods to be sold. The solution that addresses the root problem of consumerism is to only produce what can actually be bought. What're some of the obstacles with framing the problem like this?

Definitely, the ideal solution to removing excess inventory is to not have the inventory manufactured in the first place. Some businesses can have a made-to-order model for example. However, the reality with commerce is that consumer preferences are always changing and businesses are incentivized to grow their top-line [revenue]. Talking to retailers, some of the things they say are that buyers aren't taking enough risks if there isn't overstock and things like returns will always exist as long as consumer preference (e.g. ability to return, inventory that they would want to buy) is prioritized. Things like demand forecasting also don't take into account things like failed purchase orders, etc. In my opinion, the best solution is for brands and retailers to "mature" - have good disposition plans where they can take risks with their inventory to better serve their consumers but have a guaranteed outlet to move their excess inventory while having their numbers in check without having to do anything drastic like trash/burn their inventory. This playbook/value-chain of inventory is healthy for retail to allow a focus on the consumers while having a clear outlet to move the goods.

Take Back

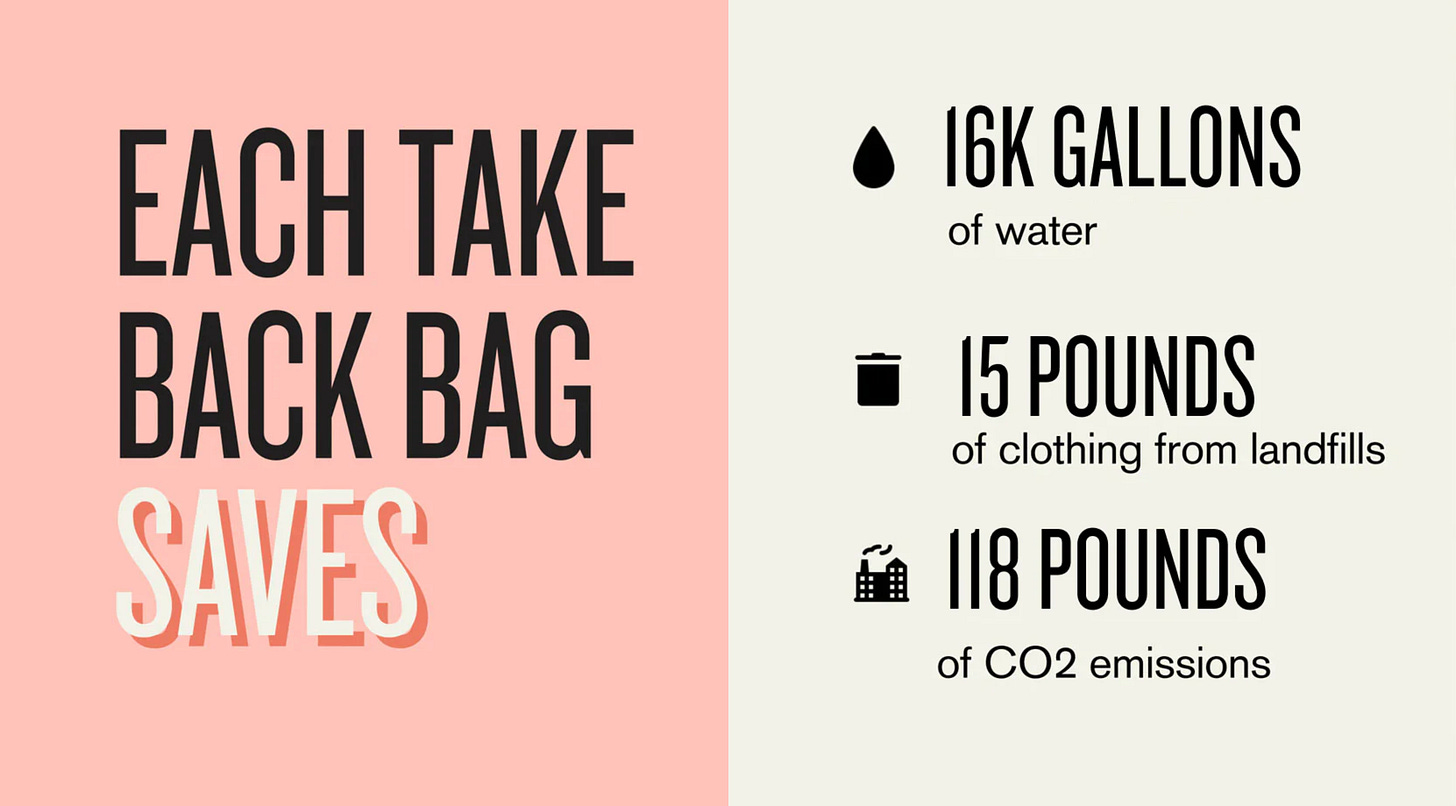

For Days is a brand that sells clothing made with 100% recycled materials. But they might be better known for their Take Back Bag, a $20 empty bag that you fill with your unwanted clothing. Neither the brand or condition of the garments matter because the items are going to be recycled. In exchange, just for buying the bag itself, the customer receives $20 in store credit so it seems like a decent deal. They claim that out of all the Take Back bag items, 50% are “downcycled into shoddy, rags & insulation”, 45% are resold, and the remaining 5% are trashed. I wonder how they’re able to resell such a high percentage of items considering they accept any brand’s clothing.

This gets at a key issue with the Take Back bag approach. From Chloe Songer, co-founder of SuperCircle, a fashion recycling software company:

One of the biggest problems right now is sorting because if you take a grab bag or a 'mass' bag and you don't know what's in it. Most of those items end up having to go through down cycling waste streams.

By integrating with brands’ order management system and scanning consumer email history to pull the exact items, SuperCircle is aiming to supercharge the textiles recycling process:

We know product data, the entire material breakdown. We are tracing them back to our warehouse [and] the system spits out a set of rules based on the product data, or the fiber data.

I’ll admit I’m still skeptical about how much this will impact overall emissions since a brand’s order management software and consumers’ email history are disconnected from ERP software and the overall supply chain. There’s also the reality that many clothing items today are constructed of a variety of materials in which case knowing the optimal sorting route has a reduced value proposition.

Signs of progress

While startups like Treet and Glimpse build software, there are also plenty of brands that are directly taking initiative:

PAKA makes clothing from alpaca fur. By working closely with a local non-profit, they’ve been able to employ 100+ local Quecha women and pay them 4x the family living wage.

Mother of Pearl is a luxury British brand run by Amy Powney who, in the documentary Fashion Reimagined, explores what sustainable fashion actually means and asserts “Nothing is sustainable.”

ALOHAS makes predominantly women’s shoes and offers 30% discounts for pre-orders on select styles. By having sales committed upfront, they’re able to better forecast demand and produce at volumes closer to true customer demand.

I also asked my friend and fashion designer Queenie Hsiao to highlight some specific designers. Here’s what she had to say:

Stella McCartney is a trailblazer in sustainable fashion, and has been a leader in promoting eco-friendly materials and ethical production practices since the launch of her brand in 2001. She pioneered the use of alternative materials, such as recycled polyester and vegan leather, and has partnered with organizations such as the Sustainable Apparel Coalition and Canopy to promote sustainability throughout the industry.

Christopher Raeburn is a British designer who has made sustainability a core part of his brand since its launch in 2008. He’s known for his innovative use of upcycled materials, such as decommissioned military parachutes and life rafts and produces his collections in small batches to minimize waste.

Bode is a New York-based brand specializing in handmade, one-of-a-kind garments. The brand uses upcycled and vintage materials and produces its collections in small batches to reduce waste. Bode has collaborated with the Natural Resources Defense Council and the New York City Department of Sanitation to promote greater sustainability.

Predictions and Open Questions

There are several startups that enable brands to offer customers the option to purchase carbon offsets to make their order “carbon neutral”. I’m skeptical that any of these work out in the long run because the entire business relies on consumers voluntarily paying more at checkout.

It’s great that individual brands are spinning up their own sustainable initiatives. However, things like Take Back bags and Trade-In programs will take a while to scale and in the short-term, the most immediate opportunity lies with the world’s largest retailers. What should Wal-Mart and Amazon do to reduce their share of emissions?

My friend Varun Agarwal is a former software engineer on the Sustainability team at Amazon and mentioned one example: Ship In Your Own Container. “Amazon is trying to reduce the amount of packaging so they’re working with suppliers to create custom shipping solutions. For example, Gillette was one of the first companies that Amazon worked with. Instead of the giant cover boxes that you usually receive, Amazon is working with Gillette to design shipping solutions that won’t require these boxes.” It definitely makes sense to not put a box in another box just like how we don’t wrap fresh oranges with plastic wrap.

How can we “price in” the environmental cost associated with the production of every clothing item? A $2 white tee from H&M doesn’t actually cost $2.

How can digital experiences reduce demand for material possessions? We already have virtual backgrounds. Are we going to have virtual clothes on Zoom? How can we reduce return rates by accurately measuring a person’s fit with computer version?

What sharing economy businesses can be created that offer the same utility of possession without actual ownership? For example, kids’ toy subscription boxes make sense because kids grow and change interests frequently.

Conclusion

My friend Olina told me “Everyday I wake up and I’m peer pressured to consume.” Whether it’s billboards on highways or ads on every other Instagram story, everywhere we go, we’re told to buy. Resisting impulse buying and opting for more durable garments is helpful, but ultimately not enough. Producing anything, even the most sustainable garment, comes at a cost. Sustainability is not about more thrifting. Or more Patagonia. Or more recycled materials. True sustainability is intentional consumption. It begins by deeply questioning whether the next purchase serves a true need.

🙏 Special thanks to Tiffany Yue, Kayla Brown, Sonia Yang, Akash Raju, Varun Agarwal, and Queenie Hsiao for their perspectives!

Awesome write up, Matt. Another related issue is the cost of returns both to the retailer and the climate. Consumers are now used to buying three of everything knowing they can easily return what they don’t need. Amazon is starting to charge for some returns but more can be done: https://www.businessinsider.com/amazon-charging-returns-fee-ups-store-report-2023-4

In the end, you are right - we need more mindful consumption and not treatments for the symptoms.

This is such a great deep dive into fashion that included a wealth of new information. I appreciate the perspective of making sure every purchase of intentional and serves a need. I love seeing all the startups trying to tackle the related environmental challenges. I'm also inspired to keep mending good clothes that can still be fixed for longer life...a habit I try to model for my kids. Another great post Matt! Thank you 👍