First things first, I just wanted to say a sincere thank you for reading Build in Climate 🙏. It’s been ten months since I quit my job as a product manager to pursue something in climate and it means a lot that you take the time to read this newsletter. We are now 612 subscribers strong!! With that in mind, I’d like to issue a challenge. If we can reach 1,000 subscribers by the end of the year, I will ski a double black diamond shirtless. It’s an ambitious goal, but so is decarbonizing the entire economy.

I appreciate y’all! Let’s keep the momentum going.

Now let’s dive into this week’s newsletter on healthcare, something I’m stoked to share, especially because it is so underdiscussed.

Growing up, I hated getting my blood tested because I was so chubby that the nurse would have to prick my little arm multiple times just to find the blood vessel. In my teenage years, I tried avoiding the dentist as much as possible because they’d always scold me for not flossing daily. Now that I’m an adult with visible veins and improved dental hygiene, I no longer feel the need to avoid medical professionals. In fact, once I learned that the US healthcare industry is responsible for 10% of overall domestic emissions, I knew I had to dig in and learn more.

With the help of Betty Chang and Chethan Sarabu, I put together this overview on Climate x Healthcare, which I think is one of the most overlooked areas in climate tech. These two have quite the stacked background. Betty was most recently Chief of Staff at a healthcare startup and also put together this wonderful deep dive on Climate action in healthcare. Chethan is currently Director of Clinical Informatics at Sharecare and is also a Pediatrician at Stanford Medicine.

Today we’ll cover:

Why the US healthcare industry is responsible for 10% of overall emissions

Climate Mitigation via anesthetics, asthma inhalers, plastics, carbon account, and supply chain

Climate Adaptation via wildfires, heat, and connecting environmental data with healthcare data

Tangible solutions and how to implement them

The Problem

The initial sticker shock that the US healthcare industry contributes 10% of overall emissions is less surprising once you remember that the sector also represents 18.3% of GDP. That’s not really a valid excuse though because with just 4% of the global population, the US healthcare industry disproportionately contributes 27% of global healthcare emissions:

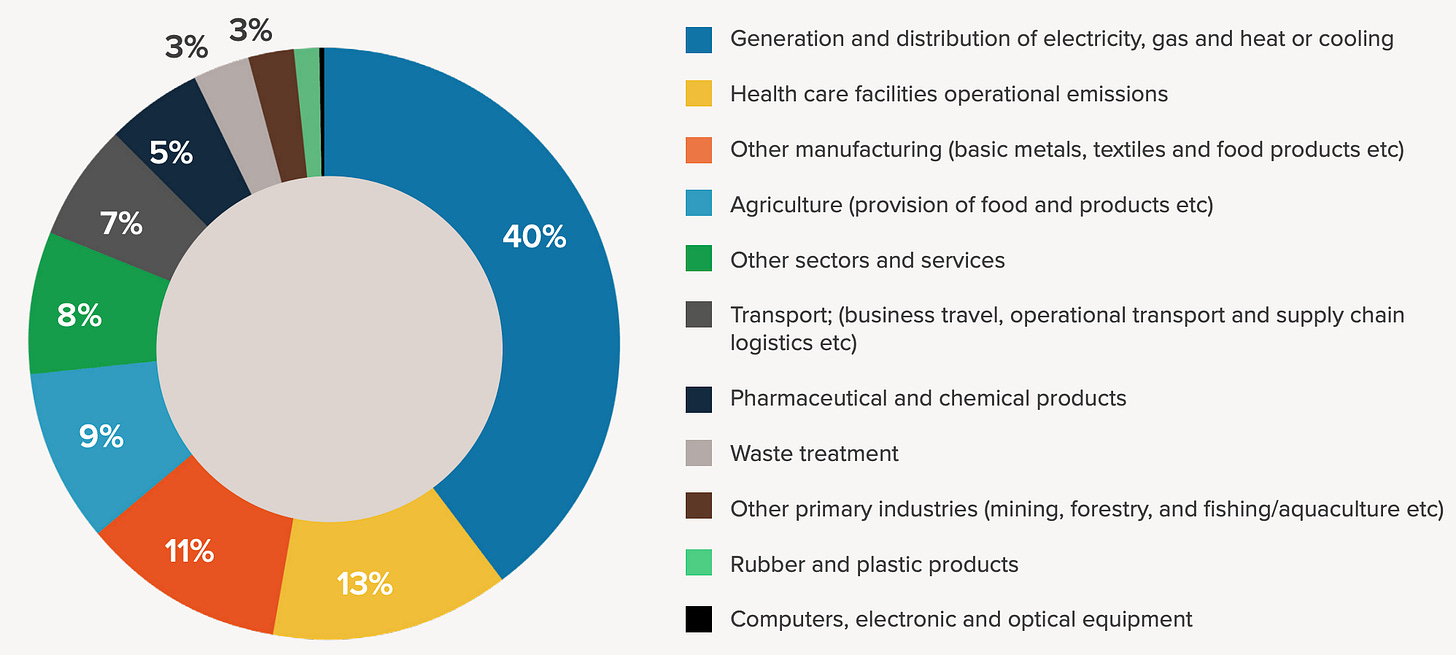

Zooming in, we see that the majority of global healthcare emissions come from energy, followed by facility operations, manufacturing, and food:

There are a few broad reasons that explain the high emissions from the healthcare industry, particularly in the US:

First, the combination of private and state-led public programs creates complex incentive structures which result in multiple parties not moving together in lockstep. For example, moving from single-use material to sterilized equipment would require coordination across many layers of complexity in order to be fully adopted. The clunkiness of this tangled system of systems is already evident with staggering statistics. The same inefficiencies that drive 30% of all health care to be unnecessary or wasteful are also generating excessive emissions and pollution.

Second, the industry suffers from interoperability silos. Patient data is stored on an Electronic Health Record (EHR), but that information isn’t easily sharable. The largest EHR companies have closed off their data infrastructure, which results in the “walled garden” problem. Without real-time open access, every layer across the healthcare stack lags behind. Optimization opportunities are stifled by the rigidity and opacity of monopolistic behemoths.

Third, like other longstanding, bureaucratic industries, change is met with inertia. For example, if you wanted to change the type of inhalers or anesthetic gases you're using, the pre-existing supply chain purchasing agreements may impact pharmaceutical companies that are creating those products.

Fourth: awareness. Chethan told me: “I think the awareness that healthcare contributes so much to greenhouse gases, especially in the US, is still relatively new. Most doctors, even hospital leaders, are really not aware of the greenhouse gas impact of health care.”

Lastly, the healthcare industry is primarily focused on saving lives. As it stands today, healthcare orgs aren’t incentivized to market themselves as greener because they don’t actually make money from being greener. At the end of the day, health customers (patients) care more about the quality of care (can they treat me effectively) and convenience (how close is the facility) than the hospital’s emissions profile. Also, despite what mainstream media makes it out to seem, the healthcare industry is a tough business (40% of hospitals aren’t profitable). Until healthcare outcomes and sustainability practices converge further or incentive structures change, consumers will continue to make healthcare decisions that optimize for their individual outcome, which I think is fair.

What makes healthcare interesting from a climate perspective

While the healthcare industry contributes emissions, it’s also often the first-in-line in experiencing the effects of climate change. From what I’ve seen, healthcare may be one of the few industries that has its hands full with both climate mitigation and adaptation. Transitioning to a net zero future will require the industry to decarbonize, but also prepare for an increasingly scary stream of demand to treat the effects of wildfires, heat, and other symptoms of an ecological crisis.

In writing this, I realized that there’s a gap between the healthcare and climate communities. The vast majority of clinicians are not actually thinking about climate mitigation or adaptation. There’s a small percentage of healthcare professionals which is now forced to pay more attention due to being on the frontlines of climate disasters, but most are unaware of the climate implications in healthcare. Unfortunately, as the climate crisis continues to unfold, the healthcare industry will increasingly be under the spotlight for climate mitigation and adaptation.

On the flip side, the climate tech scene rarely ever acknowledges the healthcare industry and tends to orient itself towards mitigation solutions (decarbonization, electrification, carbon removal) rather than adaptation. Perhaps that’s because mitigation is perceived as more directly solving the problem. Ultimately both mitigation and adaptation pathways will be needed because a) we need to solve the problem and b) the problem will take a long time to fully solve.

Mitigation

When it comes to reducing emissions within the healthcare system, there’s a plethora of solutions. To highlight a few, I’ll briefly cover anesthesia, asthma, single use plastics, supply chain, and carbon accounting.

Anesthesia

Anesthetic gases are a marvelous invention that allow us to receive surgeries that would otherwise be prohibitively painful. Unfortunately, some of them are quite bad for the environment and inevitably get emitted into the air during surgery. For example, desflurane, an inhaled anaesthetic agent, has 2540x the global warming potential of CO2 over 100 years (GWP100). The good news is early advocates from within the healthcare industry are finding win-win-win situations that reduce emissions and produce meaningful savings while maintaining patient efficacy. One case study to highlight is the work of Dr. Chesebro at Providence. From his work in anesthetic greenhouse gas emissions, “Providence has decreased greenhouse gas emissions from anesthesia by 78% and reduced overall carbon emissions by 11.5% by the end of 2022 compared to our baseline year of 2019. The reduction produced annual savings of $3.5M for anesthesia and a total of $10.8M compared to 2019.”

Asthma

Chethan: Inhalers are a really particularly double-edged sword for people with asthma or COPD who are exposed to wildfire smoke. They may increasingly rely on an inhaler to help them deal with climate driven health change. At the same time, certain inhalers are actually really potent greenhouse gases, much more so than methane or carbon. The most commonly used type of inhaler works by having a gas canister, and it's called a metered-dose inhaler. So when you puff it to get the medication, it releases some gas into the atmosphere that's quite potent. Other types of inhalers called dry powder inhalers or mist inhalers don't use that same greenhouse gas.

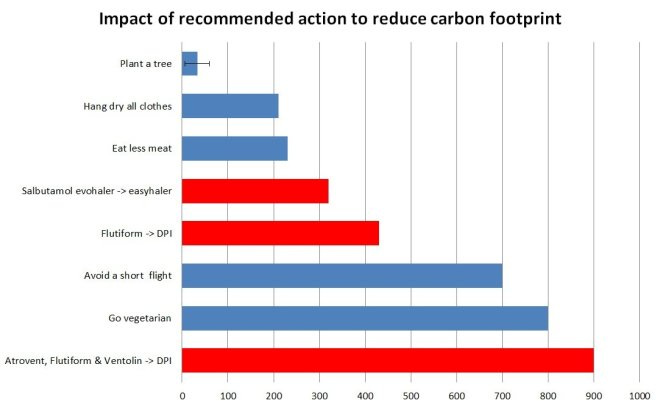

note from Matt: Switching inhaler types can reduce an individual’s carbon footprint more than going vegetarian 🤯

Single-use plastics

At first glance, the need for safe patient outcomes seems to be at a crossroads with reducing single-use plastics. I sure am thankful I’m treated with clean equipment whenever I see a bunch of plastic wrapped being opened up at the doctor’s office. The assumption that safe, clean, and effective health care must be delivered with single use materials is starting to unravel. One case study looked at the environmental impact of cataract surgery at the Aravind Eye Care System in southern India. By sterilizing reusable instruments, Aravind was able to produce comparable outcomes as the United Kingdom’s health system with just 5% of the carbon footprint. Although shifting the US healthcare system towards reusable materials would require big, slow stakeholders to move together, this example shows that it may very well be worth the effort.

Supply chain

The healthcare industry has an obvious requirement of always having materials and equipment in stock in order to provide care. We saw how disastrous it could get during COVID when basic PPE was in shortage. Due to this fundamental constraint, combined with legacy systems, healthcare organizations purchase materials in slow, long-term cycles. It’s not like how you or I can make last minute purchases on Amazon and get it the next day. From a climate perspective, inefficient purchasing behavior from inaccurate forecasting results in wasted supplies and expired materials.

Carbon

There are tailwinds behind decarbonizing healthcare. The Department of Human and Health Services led the climate pledge to reduce emissions by 50% by 2030 and achieve net zero by 2050 — with 100+ organizations already signed on.

The vast majority of emissions (71%) in the healthcare industry are Scope 3 emissions. This type of emissions is notoriously difficult to accurately track and with such a high proportion, legitimate carbon accounting is much needed. Given the sheer size of the industry and the primary focus on caring for patients, I foresee increased demand for carbon offsets and removal because the industry won’t be able to transform overnight.

Betty: From my conversations with healthcare execs, the most attractive carbon offset projects to healthcare orgs are local and community-based. Improving the health of the community has co-benefits because community health and resilience initiatives are often a dedicated function within a health system with their own budget.

Adaptation

Shifting gears to adaptation, we’ll look at how human health is already being impacted through the lens of wildfires, heatwaves, and lack of environmental data in healthcare systems.

Wildfires

If you’ve ever experienced wildfire smoke in your neighborhood, then it’s obvious what negative effects it might have on our health. But wildfire smoke harms us beyond just coughing, bloodshot eyes, and difficulty with breathing. In a California study between 2006 to 2012, wildfires were linked to premature births. During this year’s streak of wildfires in Canada, emergency departments saw an increase of 17% in asthma-related visits. While those who are healthy and privileged can avoid breathing in wildfire smoke from the confines of their homes with air filters, those who have health conditions or lower income will disproportionately suffer. For a more take on wildfires, you can check out my blog on through-hiking 22 miles in the Enchantments while smothered in smoke.

Heat

In June of 2021, the Pacific Northwest experienced a heat dome with trapped hot air resulting in 118°F days. On the hottest day, June 28th, there were over 1,000 heat-related visits to the emergency department. Compared to 2019, there were only 9. Hundreds of people died, most of which were home alone without air conditioning. People say that the four human needs are: food, water, air, and shelter. Sadly, we soon may need to add “air conditioning” as the fifth.

Chethan: A lot of people were getting heat-related illnesses like dehydration or heat stroke and didn't have a place to go to so they ended up in the emergency department. That huge spike actually affected people coming in with heart attacks and strokes to the point where they couldn't be seen on time. If the people with milder illnesses were able to go to a community cooling center to get air conditioning and IV fluids, then there would be more resources to treat those with heart attacks and strokes.

Connecting Data

In my conversation with Chethan, I learned that virtually no healthcare systems have access to or incorporate environmental data. A concrete example is in the case of asthma-related visits, there’s no system of record that feeds in weather or AQI data so that a clear association can be drawn between the air quality and this specific type of visit.

Chethan: Right now, if someone came in to the emergency department with an asthma exacerbation because they were exposed to wildfire smoke, when you look at their note, there might be a part of the note where in the free text section, it might say, “Patient was exposed to wildfire.” But then if you look at the structured data part of the note, (the code that gets identified), it'll just say asthma exacerbation. It won't have anything attributable to the wildfire.

This big problem of lack of environmental data in healthcare can be addressed in two ways. To tackle the free form text sections, LLMs can be used to detect key words and phrases that can link certain environmental conditions with the patient. To address the structured data, physicians need to advocate for updating legacy coding systems like ICD10, CPT, and SNOMED to incorporate environmental scenarios.

How to create action within the healthcare system

A solution is only as good as its potential impact multiplied by the feasibility of adoption. For an industry that is so culturally entrenched and adapts at the speed of molasses, any proposed change should be properly evaluated through the lens of feasibility. With Betty’s help, we brainstormed a stack rank of solutions for healthcare systems to consider in descending confidence in feasibility of adoption:

Energy reduction and electrification

Recycling and Reducing food waste

Anesthetic gasses

Single use plastics

Transportation routing (non-emergency medical transportation)

In-person appointments that could be done via telehealth

Unnecessary appointments / treatment (~30% of all appointments)

Unwalling the Walled Gardens (EHRs) - the data opaqueness / challenges with interoperability could be solved with carbon accounting or other solutions

How to implement

While change often starts out with a climate champion among the rank-and-file, it takes buy-in from higher-ups to move the needle. Here is the simple four-step playbook to enact change from within:

Evidence-based research trials that clinicians actually trust.

Show that proposed solution is just as effective, if not better.

Rally the troops and decision-makers. Convince the leaders to adopt these practices by demonstrating the financial ROI.

Educate, train, and advocate the healthcare workforce (Betty: Healthcare workers are really burnt out in the US, we need to find ways to change their workflows in an already rigid industry).

Parting thoughts

This is yet another example of climate being a theme, not an industry. By viewing climate as a future decarbonized state or transitionary process to get us to net zero, we can analyze specific sectors and find unique pockets of opportunities. In the case of Dr. Chesebro, he was able to find a solution that reduces emissions without sacrificing profits or treatment outcomes.

As much as we should remain laser focused on reducing emissions, I believe we’ll begin to see more appreciation for climate adaptation solutions. We will inevitably need to adjust our way of living to the reality that we’ve created.

In the past, we’ve chosen human progress over environmental wellbeing. But now we’ve realized that planetary health and human health are deeply intertwined. In the coming years, I hope we act with that in mind.

Further Reading

Climate Health Innovation & Learning Lab (CHILL) - Betty and Chethan are both involved!