🥩 Cultivating awareness for lab-grown meat #012

exploring the future of meat from an omnivore's POV

TLDR: Meat still dominates our diets because there are no worthy contenders, yet. Cellular agriculture AKA lab-grown meat is still a moonshot, but with sufficient time and capital, it’s inevitable.

Every time I’ve driven down I-5 from the Bay to LA, I seriously question why I still eat meat. I wish I could say it was the hours of solitude that provided ample breathing room to contemplate the health, ethical, and environmental impacts of animal agriculture, but that would be a lie. It’s more external and a bit suffocating. You see, about halfway in, I inevitably end up by Harris Ranch, California’s largest beef producer. They churn out 150 million pounds of beef per year, earning the nickname ‘Cowschwitz’. Thus, you smell it before you see it. Even with the car windows closed for aerodynamics and A/C, the putrid fumes ooze on in. As the smells of ammonia from concentrated urine and raw manure make my eyes water, my hands tighten on the steering wheel and morals get cross-examined.

I’m admittedly a reluctant omnivore. I still consume meat, eggs, and dairy sometimes even though I’m aware of the impact and of my lactose intolerance (ice cream is my kryptonite). I’ll even occasionally partake in the worst of them all: methane-burping beef (70% of livestock emissions are from beef and dairy cattle).

Although I’ve dabbled in going cold turkey and made strides in reducing overall meat intake, I still can’t seem to give it up. The reality is meat tastes good (and we’ll get into why this doesn’t need to be proven wrong in order to transition the meat industry). While this results in cognitive dissonance given my passion for climate, it also gives me the opportunity to examine this complex, societal problem through my individual behavior. I probably won’t be able to convince any Liver King fanboys or raw vegan hippies, but I can appeal to the majority.

In this piece, I cover the climate problem with animal agriculture, how cultivated meat is the next exponential technology after solar and genome sequencing, and what opportunities lie ahead. Hopefully I can be sufficient with stats and science so I don’t have to cover my body with fake blood and lie outside a butcher shop like some alumni from my alma mater (go bears!)

Problem

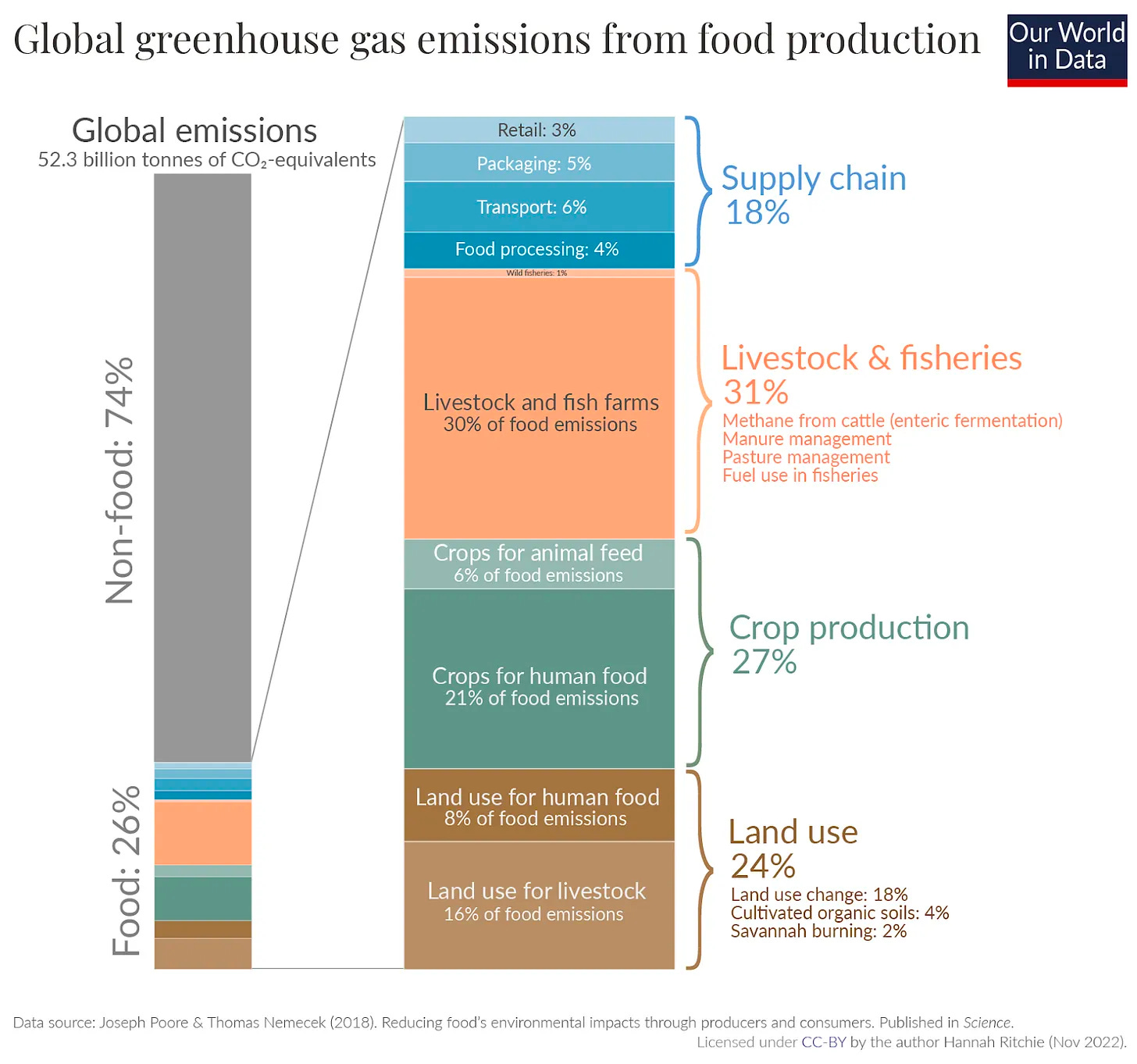

There are a lot of issues with how we currently produce food. Feeding the world’s population constitutes 26% of global emissions, of which 57% comes from livestock. If you’re doing the math, that’s 15% of overall emissions or 4x worse for the planet than airplanes.

But what if the nutritional value justifies it? We can’t just eat leaves all day. Sadly for the gym bros and carnivores, the math doesn’t check out. We use 77% of agricultural land for animal products, yet only 37% of our protein comes from meat & dairy. From a pure calories perspective, meat also doesn’t make much sense. It takes 100 calories of grain to produce 12 calories of chicken or 3 calories of beef. As a result, two-thirds of all crops are produced for animal feed and almost 80% of agricultural land is livestock-related even though it contributes only 18% of global calories.

To reiterate the scale of this problem and why we need to embrace a “yes, and” attitude, a study found that “even if fossil fuel emissions were eliminated immediately, emissions from the global food system alone would make it impossible to limit warming to 1.5°C and difficult even to realize the 2°C target”. That’s a BFD.

We typically measure progress via tons of carbon avoided or removed as the north star metric, but that’s just one way to look at it. What we actually care about is the health of our fellow humans, other living organisms, and our home Earth. “Save the planet” doesn’t strictly mean minimizing GHGs. It’s an all-encompassing battle cry that includes prioritizing land use for living over slaughtering, keeping air and waterways pollution-free, and avoiding future pandemics. Ultimately, these things are all intertwined and unfortunately, the meat industry is failing us on all fronts.

In pursuit of growth and profit margins, the meat industry forcibly pumps animals with antibiotics from birth to death. Nearly 80% of all antibiotics produced in the U.S. are for animal agriculture. This intensive practice would be the equivalent of bathing in hand sanitizer to avoid the common cold. Although I prefer my food bacteria-free, there is a risk to dousing our food in germ-killer. Every soap bottle says it kills 99.9% of bacteria for a reason. The 0.1% survives and with enough iterations of natural selection, antibiotic resistance develops which results in black swan events (cough, cough pandemics).

Air pollution and the greenhouse effect are connected, but different. Going back to my road trip horror story, I practically choked on the thick polluted air, but not because it was densely packed with GHGs. These crowded meat prisons literally produce piles of sh*t which emit hazardous concentrations of ammonia into the air.

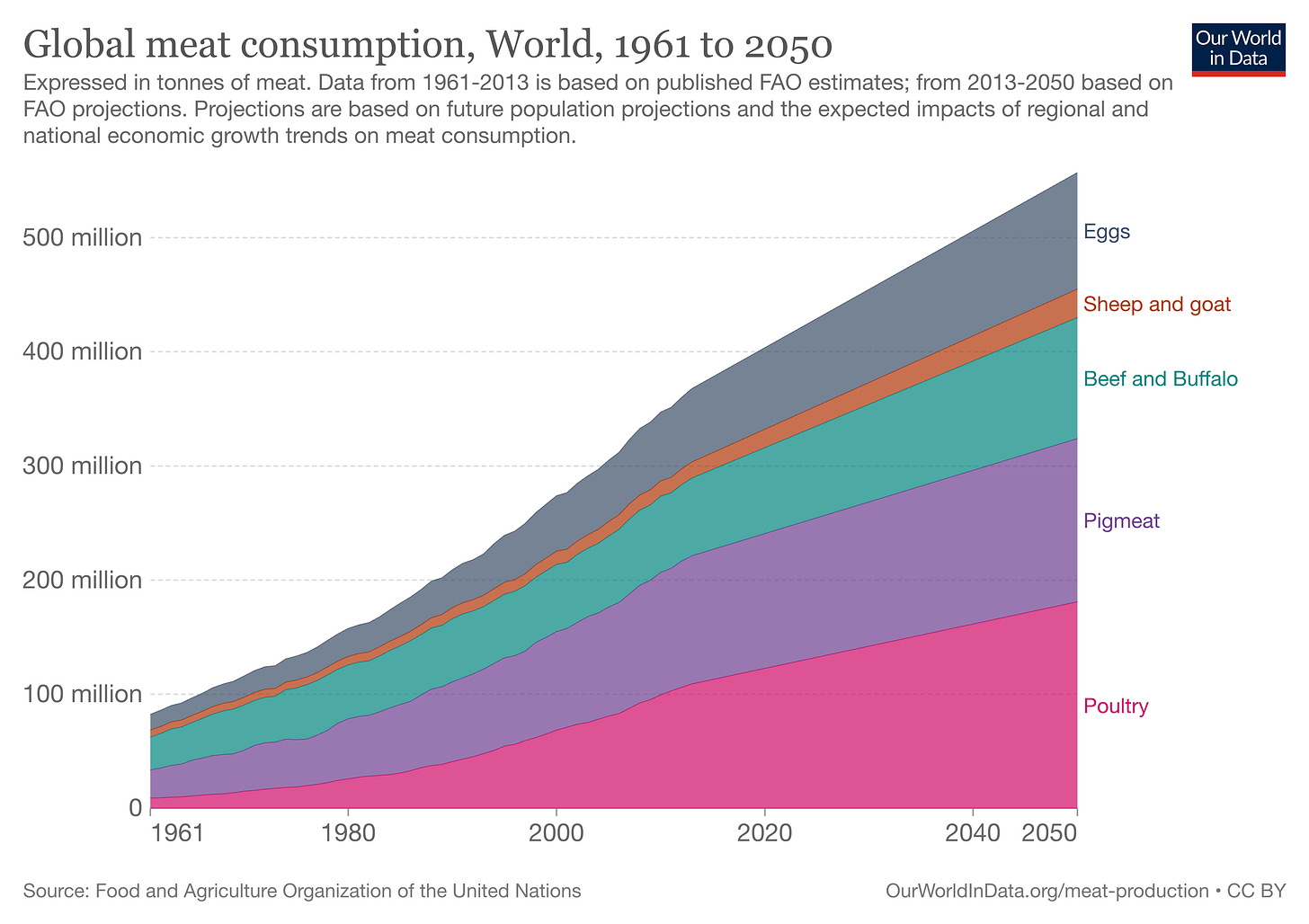

History shows that as societies get wealthier, its citizens consume more meat. We’d be more optimistic about the animal agriculture transition if we were already at “peak meat”, but sadly the opposite is true. We’re on track to eat even more meat:

Weighing in at 15% of global emissions, animal agriculture is one hefty contributor and for what? Juicy steak and a protein-rich diet? How can we still justify short-term, individual satisfaction over long-term preservation of the planet? From land use to antibiotics to nutritional efficiency, there’s plenty of non-climate reasons to get off conventional animal products. Answering why things haven’t changed much requires examining why I still eat meat.

Why do I still eat meat?

While I have gone through temporary periods of abstaining from beef or brief streaks of meatless meals, I have yet to fully commit to a vegetarian or vegan diet. Rather than profess my guilt and acknowledge the irony in writing about climate as a meat-eater, let’s look at the systemic forest instead of the individual tree.

Are the choices that we make actually made by our pure intentions or are they shaped by veiled incentives and our environment? In the Tyranny of Convenience, Tim Wu makes the case that “Convenience is the most underestimated and least understood force in the world today… Convenience seems to make our decisions for us, trumping what we like to imagine are our true preferences.” When I (and the vast majority of America.)) go out to eat, we’re greeted by a menu of mostly meat options. Trying something new, regardless of climate, requires first surmounting inertia. Experimenting (and actually sticking) with plant-based options requires convenience to switch, but also a superior or at-par product.

Simply put, today’s alternative protein products don’t meet the meat benchmarks. While plant-based meat is obviously better when it comes to the environment, the animal version still reigns supreme across protein, processing, and taste. Comparing Chipotle’s equal-priced protein options, the tofu-based sofritas has only 25% the protein of chicken.

At the grocery store, you might find brands that mimic meat with purposefully misspelled names like Chick’n, Toona, and Tofurkey. While these products wouldn’t exist unless they catered to a legitimate consumer base, I’m doubtful that these are our animal agriculture saviors. These soy-based, fake meats struggle to compete since they’re heavily processed, high in sodium, and even more expensive.

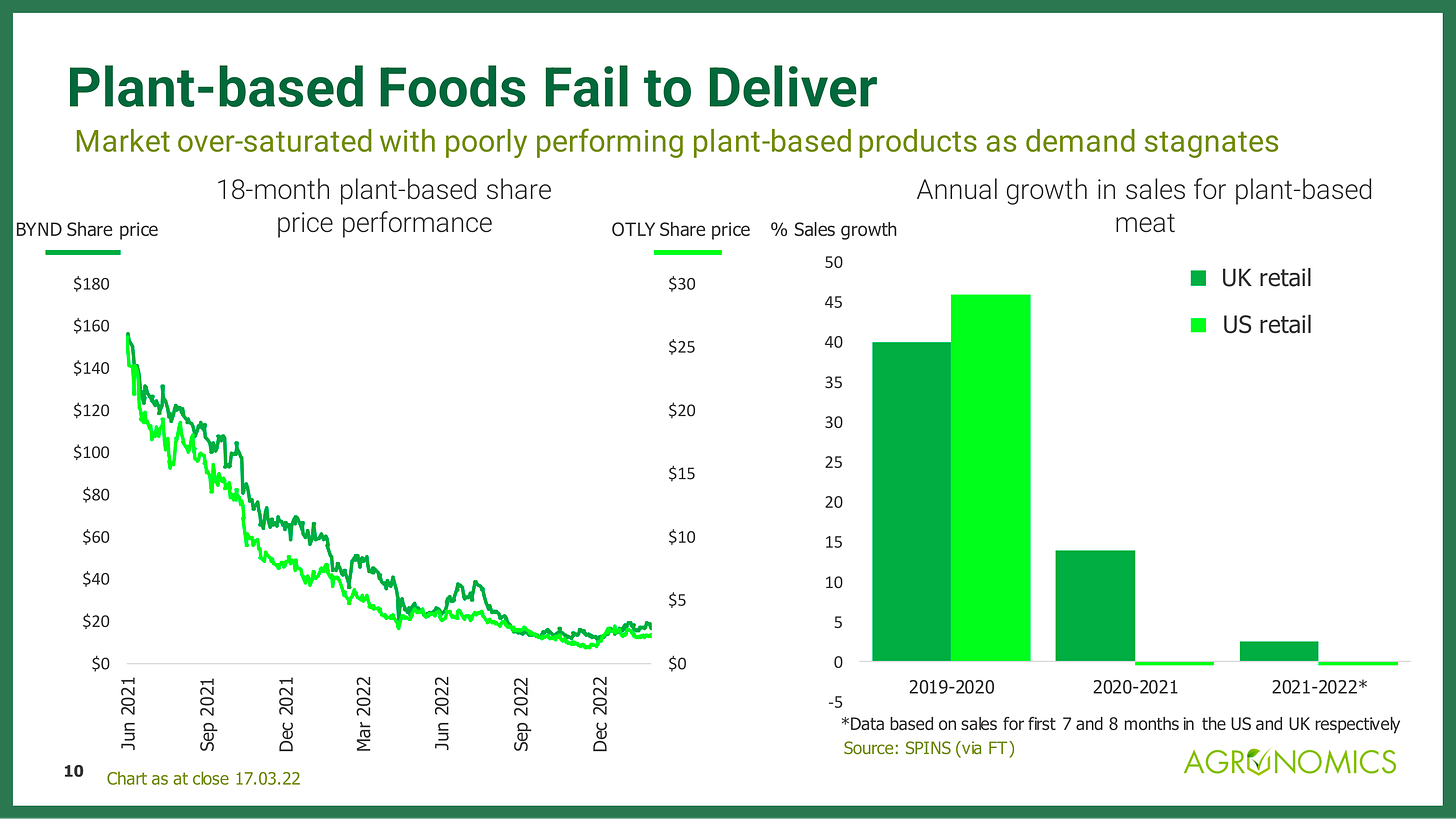

It’s impossible to discuss meat alternatives without highlighting the two players who have come the closest to breaking through to the meat-lovers crowd: Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat. At first, these two companies both backed by Bill Gates took the world by storm. But in the last couple years, the hype has sharply reversed. Since going public, Beyond’s ($BYND) stock price has declined sharply, but what’s more concerning is their decelerating growth rate:

At the beginning of 2022, McDonald’s partnered with Beyond to launch the McPlant burger, but that’s since been shut down. (note: BK went with rival Impossible and that’s still on the menu)

With inferior taste, texture, and a non-competitive price point, alternative proteins still have to reach the masses. “Despite the increasing alarm over climate change, the number of Americans who are vegetarian or vegan has remained relatively stable over the last 20 years.” That’s because the current alternatives aren’t actually meat; they’re plant-based. Even Impossible, which uses heme (what makes meat taste like meat), is still mainly composed of soy.

There is hope though. Rather than make plant-based as close as possible to real meat, some are growing meat in a lab. The end product would be nearly indistinguishable from real meat - because it would actually be meat.

Transitioning from plant-based to cellular agriculture

It’s easy to lump everything together every alt-meat company under one umbrella, but they’re not all the same. While the plant-based alternatives have failed to crack the meat market, there’s a more innovative challenger that many are betting on - cellular agriculture.

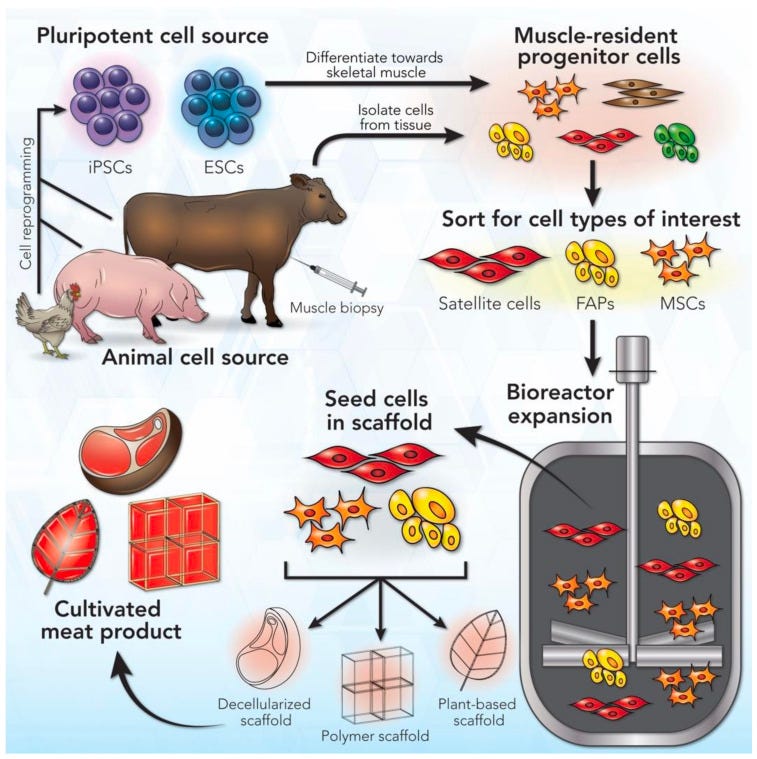

Cell-ag is the process of extracting animal cells and growing them in a controlled lab setting to produce cultivated meat akin to the real deal. Although there’s a number of challenges, this method is the most promising because it’s nearly identical to slaughtered meat in taste, texture, and nutrition.

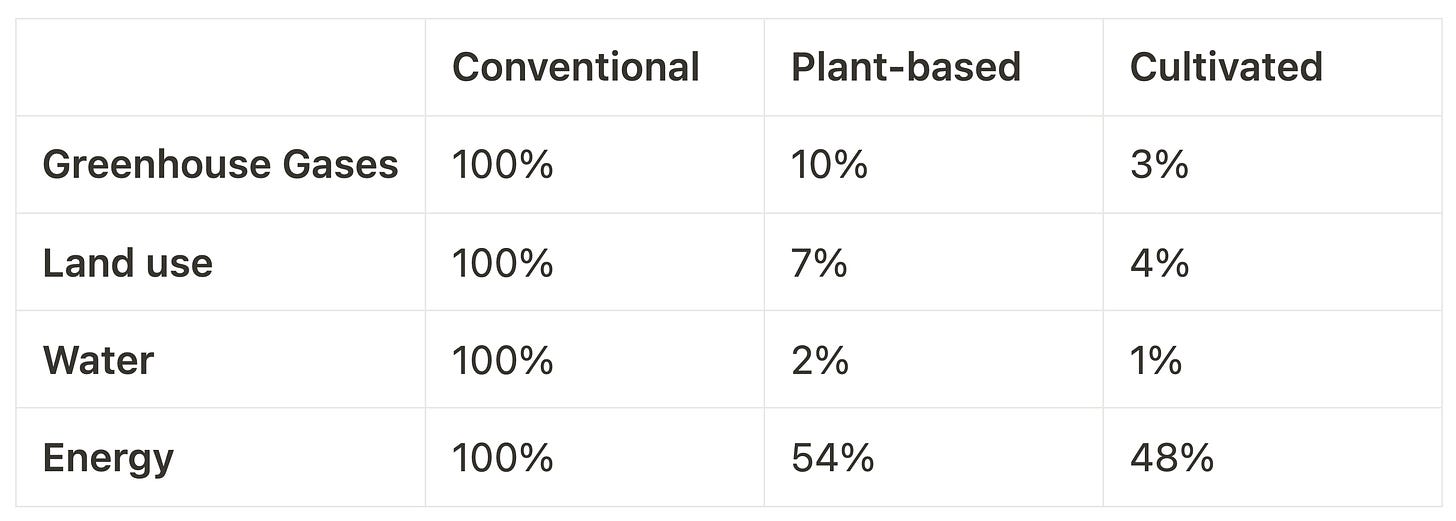

Beyond taste, cultivated meat is also the better solution for the environment. When compared to conventional methods, it’s more efficient on every aspect:

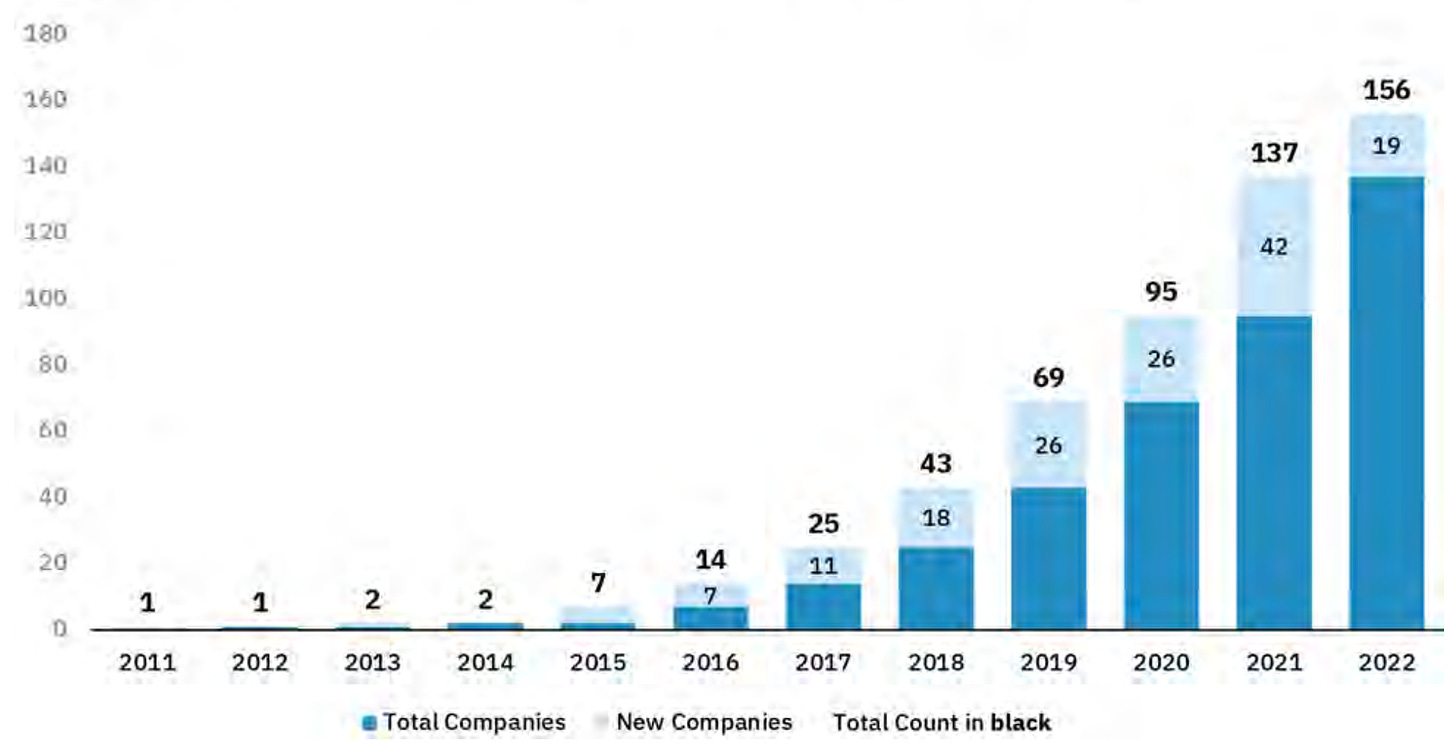

It’s great that we have this hypothetical technology that combines tissue engineering, molecular biology, and synthetic biology, but there isn’t anything substantive (yet). So what gives? To put it directly, it takes time for new industries to not only form, but also replace incumbents as entrenched as the meat industry. The cultivated meat industry is still relatively young, but been steadily growing over the last 8 years:

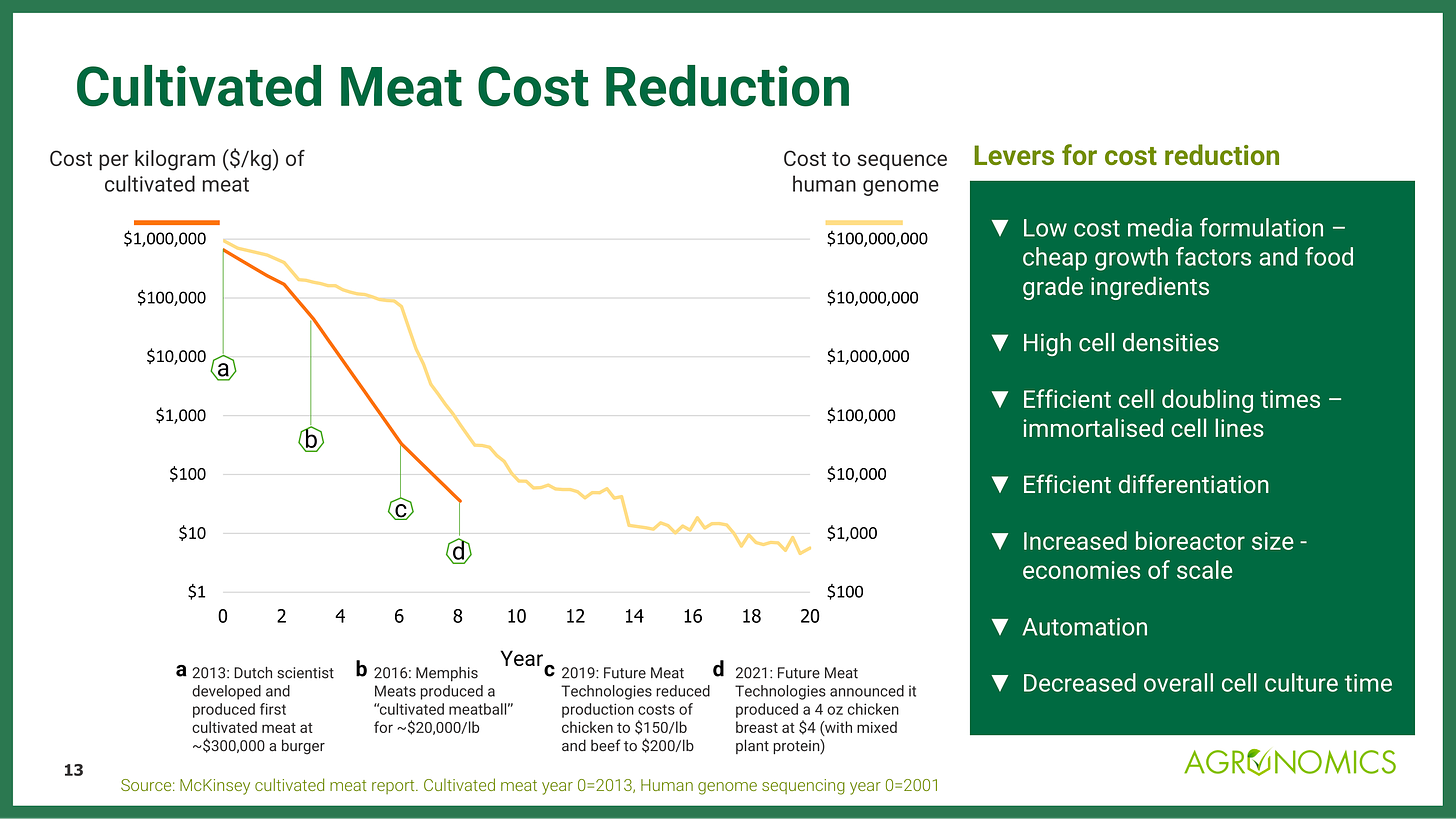

To understand “why now?”, let’s look at the history of the underlying technology. Just ten years ago, it cost $300,000 to make just one cultivated meat burger. In 2021, a cultivated chicken breast cost $4. If this trajectory continues, we can project cultivated meat will follow a similar exponential cost reduction curve as semiconductors (Moore’s Law), solar panels, and human genome sequencing:

But how does it actually work?

Manufacturing meat in a lab is no easy feat. It requires high-precision equipment operated with expertise in a controlled environment. As a result, cultivated meat production facilities look more like a pharmaceutical lab than indoor animal farm:

At a high level, the four steps to cultivate meat are Extract, Cultivate, Grow, and Combine.

Extract: It starts off with a biopsy of the animal species. Different cell types are sampled including muscle, fat, and multiple kinds of stem cells.

Cultivate: Cells are sorted and selected based on quality and purpose.

Grow: Cells are grown in oxygen-rich bioreactors called cultivators by feeding them amino acids, glucose, vitamins, inorganic salts, and other proteins.

Combine: Tissues are harvested, combined, and layered in a technique called scaffolding. This process depends on the structural sophistication of the end product. For example, hot dogs are the easiest, followed by minced products like hamburger meat, with the most complex being steak or similar products.

All this takes anywhere from 2 to 8 weeks, depending on the kind of cultivated meat (significantly faster than conventional animal agriculture).

There are many ways to slice-and-dice the meat market

Painting a picture of the alternative meat landscape requires framing the boundaries first. Generally speaking, I think anything that reduces emissions generated from conventional animal farming should count. There’s a variety of approaches ranging from direct meat replacements to individual protein types to specific optimizations that all reduce emissions in their own way.

Direct Replacements (both plant-based and cultivated)

There’s a plethora of players here tackling every meat product each in their own way. Upside Foods (fka Memphis Meats) is the OG in the space with their cultivated chicken breast. Mosa Meat is going after the beef industry with their cultured burger. Black Sheep Foods makes predominantly pea-based lamb. Meati and The Better Meat Co are leveraging naturally protein-rich mushrooms. With its hybrid approach of blending plant-based and cultivated meat, Sci Fi Foods is aiming to solve the taste problem of plant-based while avoiding the high price point of a purely cultivated product. Last but not least, there are also dozens of alt-seafood startups, like BlueNalu with their cultured bluefin tuna.

Animal Products

Even though the main product is the meat itself, there are still massive markets for meat derivatives. Whether it’s Perfect Day for whey, Zero Cow Factory for casein, or GELTOR for collagen, there’s at least one challenger looking to flip the script.

Dairy

Out of all aspects, milk is perhaps the furthest ahead in the transition. 25% of the milk market is already non-dairy. In recent years, the two largest dairy factories Borden Dairy and Dean Foods, have gone bankrupt.

But you already see it with your own eyes. When you walk into a coffee shop and order your drink, they ask you what milk you want rather than assume. You might already know about Califia Farms and Ripple Foods with their plant-based products. There’s also Remilk and Better Dairy going the cultured route.

Eggs

Whether it’s baking, omelettes or simply hard-boiled, eggs play a key role in cuisine. The biggest player is JUST with their suite of scrambled products. But there’s also my friend Grace’s chickpea-based Peggs and EVERY with their version of egg whites.

Methane

This last section is cow-specific. With the beef industry responsible for 40% of methane emissions and 6% of global emissions, there’s a ton of attention on how to reduce or even eliminate these harmful burps and farts. The least-scientific, Zelp is putting muzzles on cows.

Then there are several startups that are tackling the problem through feed additives. By supplementing animal feed with algae and other similar compounds, companies like FYTO, Mootral, Rumin8, and AlgaBio are able to reduce methane from cows by up to 85%. The biggest moonshot of them all is ArkeaBio which is administering vaccines to reduce methane emissions in cows.

How is software relevant?

Even though growing meat in a lab is largely a function of combining hard sciences with hardware, software still plays a crucial supporting role. From an R&D perspective, researchers use software tools to design and simulate cell lines. For the actual production process, bioreactors (or cultivators) are controlled via software that can manage temperature and pH balance, as well as nutrients and waste management. To manage the inflow of materials and outflow of finished product, supply chain tools coordinate logistics. In conjunction with sensors, analytics software is used to identify patterns and detect insights. To maintain compliance with the FDA and other regulatory bodies, companies need specific tools that can streamline the reporting process.

Climate is a theme, everything is connected

Although I first decided to investigate the animal agriculture industry from a climate perspective, it’s clear that there’s so much more to this multilayered, complex problem. Beyond contributing to emissions, the meat industry is responsible for other types of harm and potential risks. Growing crops for animal feed and raising the animals themselves occupies land that could be used for housing. With 80% of overall antibiotics going towards the meat industry, there’s a risk of antibiotic resistance developing. Recent pandemics (COVID-19, Ebola, MERS, swine flu) are zoonotic, meaning they originated from animals. Relying on conventional methods for meat, but also deforestation which brings society closer to wild animals only increases the odds of another pandemic. I haven’t even touched on ethics that much, but it wouldn’t surprise if in 50 years we look at eating animal meat as this selfish, barbaric act just like we have changed our views on other relics of the more primitive past.

From an individual health standpoint, there’s tons of conflict advice. Carnivores say meat is supreme while a decent number of athletes have gone vegan for performance reasons, among others. Although there isn’t consensus on whether meat is good or bad for our health, there are two anecdotes that I find fascinating. Bryan Johnson is known for spending millions a year to meticulously follow his blueprint for living a long, healthy life. His vegan diet consists of just 2,000 calories per day and is largely vegetables, nuts, and legumes. With their traditional lifestyle and only a few thousand remaining, the Hadza have become the subject of several research studies. Located in Tanzania, the group of hunter-gatherers have a healthier gut microbiomes than that of modern societies. Studies have linked their robust microbiome to a fiber-rich diet and also shown that your microbiome changes dramatically based on what you eat.

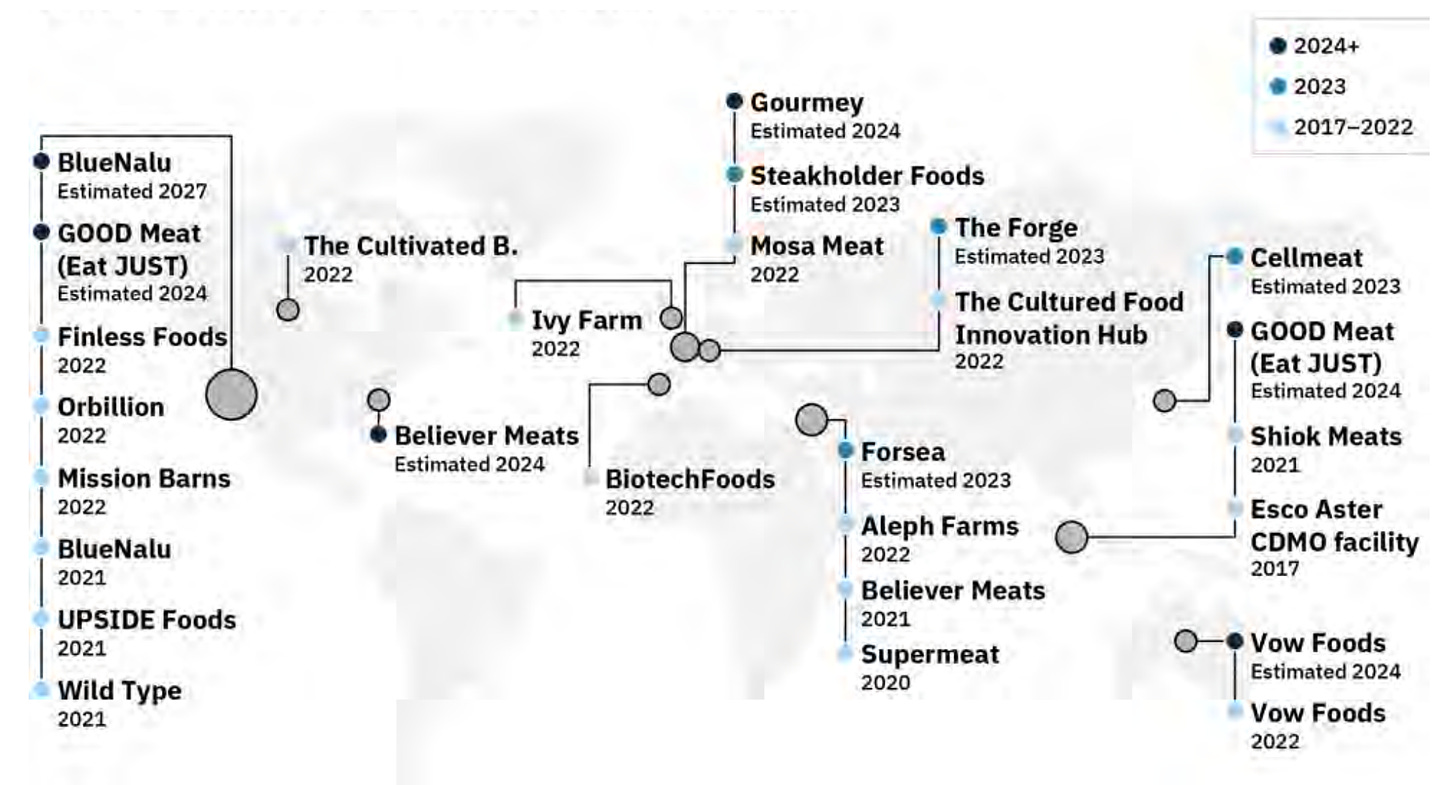

Finally, it’s worth touching on food security. With conventional animal agriculture, meat is imported because the ideal environment to raise animals may be different from where demand is. Switching to a lab-based means of production removes this constraint because you can build the production facility just about anywhere. Without a large animal agriculture industry of their own and plenty of neighbors surrounding them, it’s no wonder why Israel and Singapore have been huge proponents of the cultivated meat movement.

Current and future cultivated meat production facilities:

Open questions

Should rapidly developing countries like India, Nigeria, and China have the right to consume meat at similar levels as western societies without any pushback?

Are there any existential risks to the future of cultivated meat? It seems like it’s still expensive and there’s more improvement needed on the actual product, but that will be addressed with incremental iterations over time.

There’s at least a few climate spectrums. With energy, there’s DERs vs. greening the grid. In carbon, folks debate the necessity of pioneering removal technologies. With meat, it’s cultivated vs. plant-based meat and also lab-grown vs. improving current practices like reducing methane emissions from cows. We will try all of them, but I wonder which approach wins over the long run and to what extent?

If lab-grown is the superior way to produce meat, then what’s the equivalent for plants? Vertical farming? (the topic for the next newsletter!)

Can we just simply make plant-based meals taste better? This might come across as a joke, but consider for a second what proportion of the culinary industry and media still center meals around meat. If plant-based meals tasted as good as meat-y meals (and I’m sure it’s already happening), then I think more omnivores would convert or at least reduce.